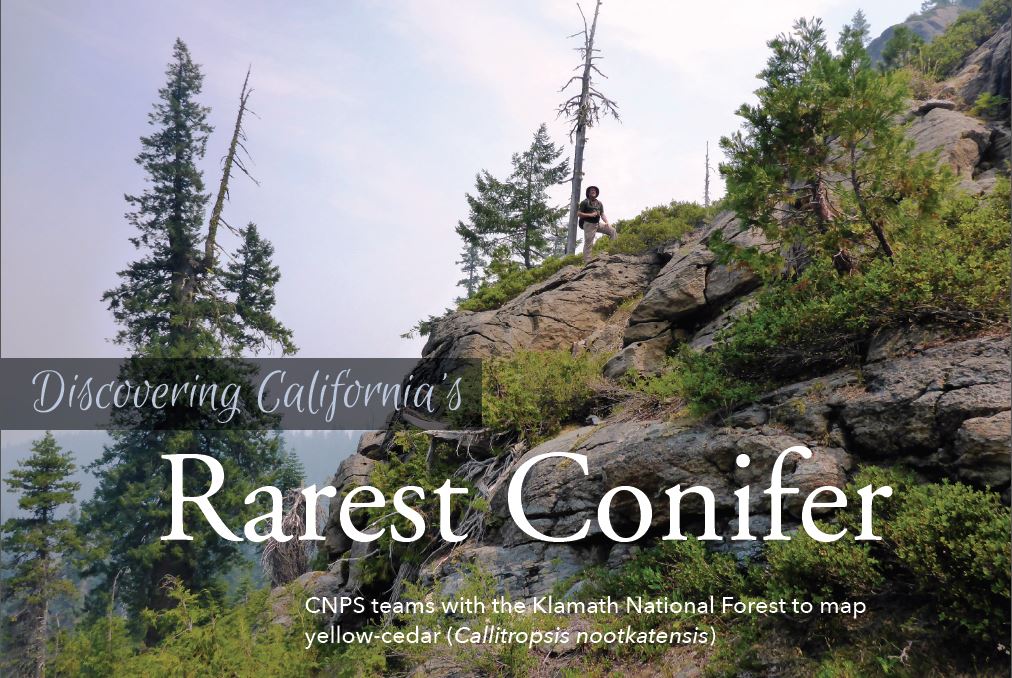

I have begun a collaborative mapping and inventorying project for yellow-cedar in California this summer. The species is a CNPS Inventory of Rare and Endangered Plants on list 4.3 (limited distribution) in the state, with only a handful of known locations. The majority of the stands are on the Klamath National Forest but a few are also on the Six Rivers. Over the course of the summer I will be visiting a number of these populations and collecting data on stand health, reproduction, and plant associates. I made the first stop of the summer at the Bear Peak Botanical Area.

Yellow-cedar (Callitropsis nootkatensis)

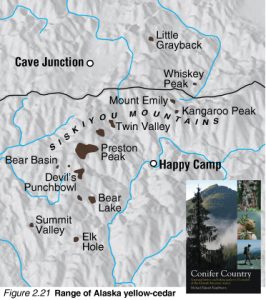

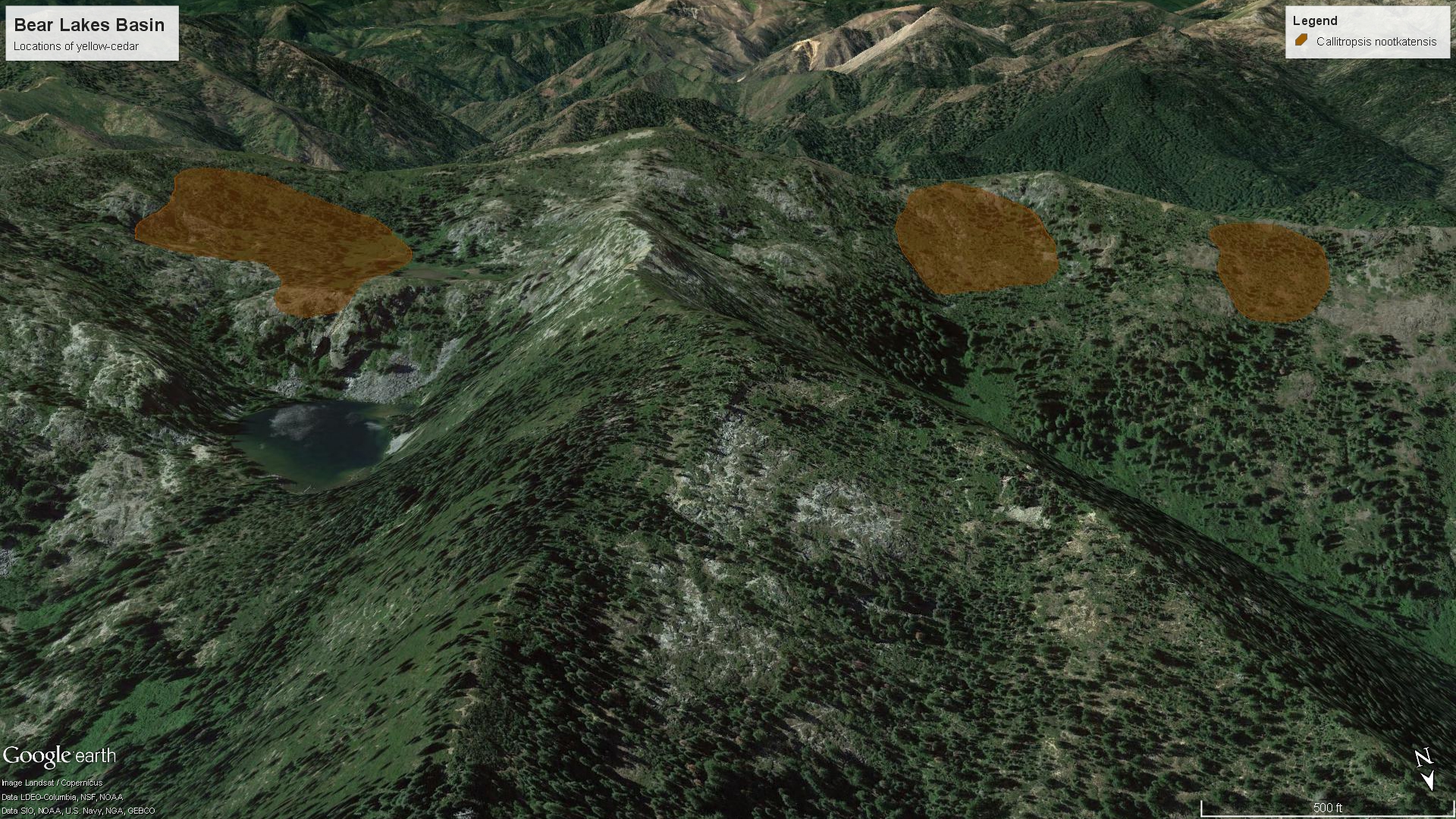

This common tree of Alaska and British Columbia south to northern Oregon is represented in the region by a few small, isolated groves. In the southern extent of its range, yellow-cedar has a unique ecological amplitude compared to habitats further north. Over most of Alaska and Canada, it is a tree of the coastal mountains, growing from sea level to 3000’. But as the species ranges southward into southern Washington and Oregon it moves upslope into cool, wet, rocky, north-facing glades where subalpine conditions prevail. This is also the case in the Siskiyou Mountains, where it is a true relict, surviving in a handful of specific microsites that maintain a cool wet climate. Yellow-cedar trees do not reach significant size in the Siskiyous—I’ve never seen one more than ~70’ tall . Although lacking size, all southern stands maintain healthy populations. They often form impenetrable, low-growing thickets along entire rocky washes between subalpine lakes.

Other “cedars” in the region that overlap in habitat with yellow-cedar have a leaf silhouette that can be described as lacy or flattened (Port Orford-cedar) and vertical (incense-cedar). With yellow-cedar the droopy foliage falls from a distinctly conical crown in a definable pattern, creating a wet and tired look. The drooping is an effective adaptation to slough off weighty winter snow without branch breakage.

Where the species overlaps with other cedars, Port Orford-cedar can be distinguished by stomatal bloom in the shape of an X on the underside of the needles while yellow-cedar has no bloom. The spherical cones are similar to those of Port Orford-cedar, but yellow-cedar has fewer than six cone scales, while Port Orford-cedar has more than six. The unopened cone looks like an armored ball because the end of each scale presents a sharply tipped umbo. Most of the year cones remain closed, like cypresses. Though cone production does not occur every year, one may find remnants on the ground from previous years—which will greatly aid with proper identification. The bark is similar to the North American cypresses but thinner. Only the juvenile bark characteristics are important in the region because trees do not get very old (or big) here—gray to brown to rarely black between scaly or shallow ridges. In the Siskiyou Mountains these three “cedars” all occur, sometimes together, making identification challenging. The real challenge lies in finding a location where the regionally uncommon yellow-cedars still survive.

This species epitomizes the rarity that makes the Klamath Mountains special. We owe it to the yellow-cedars to make sure they remain healthy in these remote and secret cirques.

Bear Peak Botanical Area

The trail to the botanical area is along a segment of the Kelsey Trail, an historic route from Yreka to Crescent City that was used for a quarter-century to support mining operations on the Klamath River. This is also a hike to the Bear Peak Botanical Area and one of the largest stands of yellow-cedar in California—along with a nice selection of other conifers. In the basin itself there are several lakes in a north-facing cirque and from the ridge above the basin there are spectacular views throughout the Siskiyou Wilderness.

I will be visiting more sites across the Siskiyous this summer and will, of course, be updating the blog.

Cool!

Michael, I have just returned from Elk Hole. There is a small but vigorous population of yellow-cedar. Most are in a tight group in a wet spot on the edge of the pond at the bottom of the hole. The tallest is probably 50 or 60 feet. In this setting, they really stand out, with an almost other-worldly appearance. The whole trail from Elk Valley to Elk Hole is a conifer lover’s delight. This is a VERY primitive trail, insanely steep at times with a lot of up and down. It can be done as a day hike, but don’t underestimate the time and effort required. It looks like a short distance on the map, but don’t be fooled. I have done a little work on the trail, reconnecting a spot where the tread had disappeared and removing obstacles, so it’s pretty straightforward finding the route and anyone should be able to get through.

And…there are now elk in Elk Hole. I observed a group of at least four on Sunday, swimming in the pond and then ambling up the mountainside to the northeast.

I live just south of Dallas, TX. I have a large Alaskan Yellow-Cedar in my back yard. It is approximately 70 feet tall and is quite healthy. It is growing near, but not in, a seasonal creek bed along with several large native Texas pecan trees. Even in drought or extreme heat years it never shows signs of stress. I have verified its identity with the Dallas Morning News’ gardening expert.