Original Publication DATE: 8/23/2010 1:54:00 PM

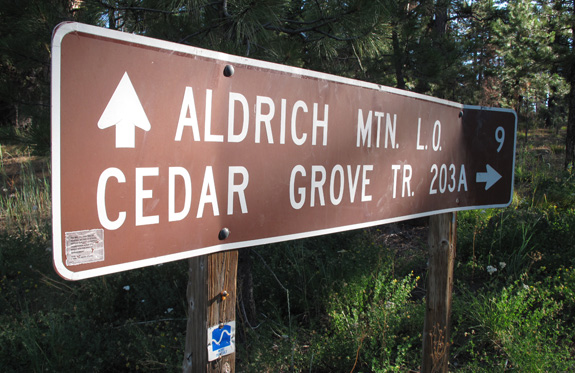

Alaska yellow-cedar (Callitropsis nootkatensis) is common tree of Alaska and British Columbia south to northern Oregon. The species is represented by a few, small, isolated groves at the southern extent of its range in California—only in the Siskiyou Mountains. However, in the arid mountains of central Oregon, several hundred miles east of the crest of the Cascade range, a 26 acre population has persisted since the Pleistocene–a relict of a time when the climate was wetter and cooler. The Cedar Grove Botanical Area in the Aldrich Mountains was a must-visit destination on a recent sojourn across eastern Oregon.

After descending from the ridge for about a mile through thick forest of lodgepole pine (Pinus contorta), western larch (Larix occidentalis), Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii), and white fir (Abies concolor) we eventually broke out onto a sunny hillside which fostered ponderosa pine (Pinus ponderosa) and western juniper (Juniperus occidentalis). I had a hard time believing we were about to see a grove of Alaska-cedar adjacent to these high desert species.Within minutes we rounded into the headwaters of Buck Cabin Creek and found the cedars. However, upon entering the grove, we discovered that most of the trees were dead. After touring the creekside we estimated a 90% mortality for the Alaska yellow-cedars while the other conifer species were faring just fine.

The mortality we witnessed was disturbing. This–the quintessential outlier population–offered a relict habitat from an ancient era finely balanced but now seemingly on the edge of extinction. This population is one that should be monitored and understood as climate change effects microsites across the West, and in fact it is being well watched. Joseph Rausch, a botanist with the Malheur National Forest, explained that in 2006 a fire was sweeping across the range and the decision was made to set a low intensity backburn through the botanical area to ‘save’ the 26 acre population. The fire moved through the understory but has since had a negative effect on the cedars. Alaska cedars have thin bark which makes them generally intolerant of fire and it appears this backburn led to their current demise.

On a positive note,seedling recruitment is being witnessed–especially creekside. However, it is concerning that since the other conifers were not effected by the fire the canopy may ultimately close over–shading the cedar seedlings out. Only time will tell. In the Klamath Mountains, at the southern end of the cedar’s range, a minimum of 9 individual populations persist. These are spread out over 50+ air miles. The scattered distribution coupled with the wetter climate virtually ensures their survival–at least in our lifetimes. But, we need to watch and understand these microsites change as we change our climate. Watching and understanding how these outlying species are affected is for our well being as well as theirs.

—–

COMMENT:

AUTHOR: Stu Garrett

DATE: 7/6/2011 1:19:50 PM

Hi Michael,

I read your excellent article in Kalmiopsis.

I visited your website.

I noted that your distribution map for Pinus contorta murrayana shows it stopping in the central cascades going north. Other distribution maps vary from that. Why the difference?

Thanks,

Stu Garrett

Bend,OR

Stu- thanks for the kind words. As far as the dividing line, most use the Columbia River to separate the species. I went with a latitude adjacent to the Blue Mountain populations–both are probably arbitrary as characteristics of the two exhibit a subtle gradient across the Cascades there.

Happy conifer hunting, Michael

—–

COMMENT:

AUTHOR: Bill Standley

DATE: 6/13/2013 1:58:46 AM

Fascinating, whilst working in the Blues, I never got around to visit the “grove”.

But speaking of the Blues, I concluded that the southern most Western Larch in N.America occurs on the slopes of King Mtn north of Burns. The general bona fides being observations in the autumn when these isolated trees stand out. What are your thoughts on this?

Bill

—–

COMMENT:

AUTHOR: Michael E. Kauffmann

DATE: 6/13/2013 1:18:02 PM

Bill- I hope to know the Blue Mountains better one day, but for now I defer to you! I’d love to see that southern-most stand of western larch on King Mountain, thanks for the tip.

—–

COMMENT:

AUTHOR: Bill

DATE: 6/14/2013 12:30:02 AM

It’s quite dramatic (for a tree person) to stand off at the appropriate distance with binoculars to the south of it when the larch are showing and see the flash spots of isolated larch.

Also …are you hip to northernmost Incense Cedar?

—–

COMMENT:

AUTHOR: Michael E. Kauffmann

DATE: 6/14/2013 1:16:05 PM

Bill- I looking into the northernmost Calocedrus decurrens once, but don’t remember the details. Remind me!

—–

COMMENT:

AUTHOR: Bill Standley

DATE: 6/15/2013 3:38:38 AM

Michael,

I believe (vs. know) Incense Cedar peters out as it progresses north in the Cascades in Oregon with the northern most in that range on the southeast slopes of Mt. Hood. BUT…..I believe the most northern are a unique stand on an island on the Deschutes River canyon north of Maupin. I drift boat by them as I was a local back then and it was referred to as cedar island.

I worked on the now defunct Bear Springs RD, compound and station is still there on the east side of the Mt Hood NF….and within that compound were/are 12 species of confider. Transition zone mixed conifer.

—–

COMMENT:

AUTHOR: Bill

DATE: 6/15/2013 3:45:28 AM

A google of Cedar Island Deschutes River will get you images.