Original Publication DATE: 10/24/2010

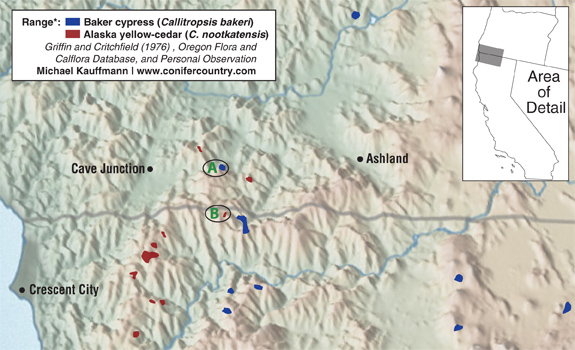

With the threat of our second significant storm of the season looming, I packed the truck and headed into a mysterious and isolated region of the Siskiyou Mountains to find two rare groves of trees and enjoy the transition toward winter. The roads are long and lonely leading south from Oregon’s Applegate Valley into the high peaks of extreme southern Oregon and northern California. This region drains the headwaters of the Applegate River where nebulous state borders are crisscrossed by wild mountains, rivers, and the occasional road. This is surely the quintessential ancient meeting ground where rare plants have hidden out for millenia–optimal environmental conditions are fostered with a unique balance of sun, soil, and water. In addition to the rare conifers under discussion one might also encounter Pacific silver-fir, subalpine fir , Brewer spruce, and Port Orford-cedar close by–not to mention the other more common species.

One quick side note with respect to the genera I present here (without getting overly detailed)–several classification schemes currently exist for these species. Alaska-cedars have been placed in one of five genera by various sources: Cupressus, Chamaecyparis, Xanthocyparis, Hesperocyparis, and Callitropsis. Needless to say, things are a bit up in the air. While these names have yet to be worked out what has transpired, for now, is one of three scenerios:

1. The New World cypresses, the Alaska-cedar, and Vietnam cypress were placed in a new genus—Callitropsis—while Chamaecyparis (Port Orford-cedar) was left alone (1).2. With the use of cladistic analysis using morphological characters others propose placing Alaska-cedar in close relation to the Vietnam cypress in the genus Xanthocyparis and keeping the new world cypresses in the genus Cupressus (2).3. Placing all of them in Cupressus (3).

The latter is probably the easiest and may ultimately be what happens. However, I am using Callitropsis because that is what I printed on my poster Regardless of names these two species could not be ecologically more disparate–new world cypresses thrive in hot, dry, and sunny conditions throughout the southwest into Mexico and Alaska-cedars endure subalpine snow-pack in wet, often rainforest-like conditions northward into Alaska. The Siskiyou Mountains are the only place in North America that these species overlap—where the Siskiyou cypress reaches the northern extent of any cypress and the Alaska-cedar reaches its southern extent. This is the region we will now explore.

Siskiyou cypress (Cupressus bakeri) at Miller Lake (Site A) | Rogue River National Forest

Miller Lake sits at the end of a logging road that was washed out a few years ago. To reach the lake it takes a 4 mile walk from the washout or a 4WD vehicle to cross the creek and drive to within 1/2 mile of the lake. It appears that some refer to this are as a Botanical Area but there is little evidence this designation exists. Regardless, it needs to be protected and studied. Refer to C.J. Earle’s Conifers.org site for more specific direction to find the grove. There is a nice 1.5 mile loop up the ridge and around the lake where many other interesting plants can be observed, including what must be one of the western most locals for Cercocarpus ledifolius. The champion Siskiyou cypress is also rumored to be in this grove.

I have only seen this series in the 10 acre stand at Miller Lake where Siskiyou cypress associates mainly with white fir and Douglas-fir in a dense north-facing forest with other conifers such as Brewer spruce, western white pine, incense-cedar, Shasta fir, and mountain hemlock also occuring. The cypresses appear to be threatened by a live rotting fungus possibly exaggerated by the cooler conditions propagated by the dense forest. In addition to the mortality, seedling recruitment is minimal here–with the exception of places that rock outcrops keep the forest more open. We may be witnessing the beginning of an extinction if fire regime is not re-established soon.

Alaska yellow-cedar (Callitropsis nootkatensis) on Mount Emily (Site B) | Red Buttes Wilderness

The north-facing cirque below Mount Emily in the Red Buttes Wilderness holds another relict stand of conifers–one of eight locations in California to see Alaska yellow-cedars. Upon finding this population I have now seen all of these locations–but there are surely more to be found. I have added three of the eight locations during my explorations in the Siskiyou Mountains over only the last several years. Sites are predictable in that they are north-facing, above 6,000 feet, hold snowpack into late summer and hence usually have steep rock faces near mountain tops. In all eight California locations seedling recruitment is flourishing and disease is not yet a significant factor in mortality. The species is doing well here.

Explore More:

- Yellow-cedar on Conifer Country

- Siskiyou Cypress on Conifer Country

Citations:

1. Little, D.P. 2006. Evolution and circumscription of the true cypresses (Cupressaceae: Cupressus). Systematic Botany 31(3): 461-480.

2. Farjon, Aljos. 2008. A Natural History of the Conifers. Timber Press, Portland, Oregon.

3. Eckenwalder, James E. 2009. Conifers of the World. Timber Press, Portland, Oregon.

4. Earle, Christopher J., Forest Ecologist, 2009. The Gymnosperm Database, <https://www.conifers.org>

Hey Michael,

I’m writing a hypothetical Recovery Plan for Baker Cypress. I’m wondering if you know of any connectivity between populations, the distance between stands for them to be considered isolated, and/or the potential distance that viable pollen can travel.

Alessandro

281-636-0804

Alessandro- Sounds like a worthy endeavor, unfortunately I do not know the answers to your questions. The two folks who have done the most work on Baker cypress are Erin Rentz and Kyle Merriam. You can follow THIS LINK to find some of their papers and possibly contact information.

Do you think yellow cedar could be grown in northern Alberta if it was irrigated?

Irrigation could be an issue. Many trees are dying at the northern range limit due to less snow and more rain. I am not a horticultural expert on the species but they do well as ornamentals in Humboldt County, California.