Original Publication DATE: 5/1/2011

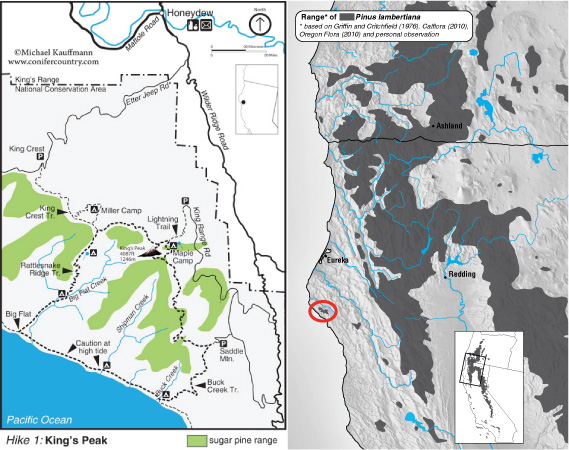

The Lost Coast presents plant associations (or lack of associates) that have long puzzled botanists. From the perspective of the conifer lover the question is: Why are redwoods, grand fir, and sitka spruce absent in an area which annually receives 100+ inches of rain, has some summer fog, and is nourished by soils from that of the central belt of the Franciscan Complex? These same conditions exist only a few mile north where redwood, grand fir, and Sitka spruce forests thrive. In the heart of this wilderness, over 20+ miles of walking, I found only two conifers. After and mentally and physically taxing journey I was left with a sense of wonder at the fortitude of the species that were present; and not the absence of the conifers unable to reside.

The weekend mission was to get into summer backpacking shape by climbing King’s Peak, then to walk 4000′ down to the Pacific Ocean to spend the night and climb back up King’s Peak the next day. Of course, I could also justify my walk by looking at plants to gain a better understanding of the phytogeography of the region along the way. While I had done this walk ~10 years ago, my first new impressions of the King Range came from the temporally variable occurrences, sizes, and extremes of the fire regime over the past several thousand years. The Lost Coast is so inaccessible that fire cannot be managed and therefore what is seen is, to a large degree, what nature intended. The mixed-evergreen forests were sculpted by fire.

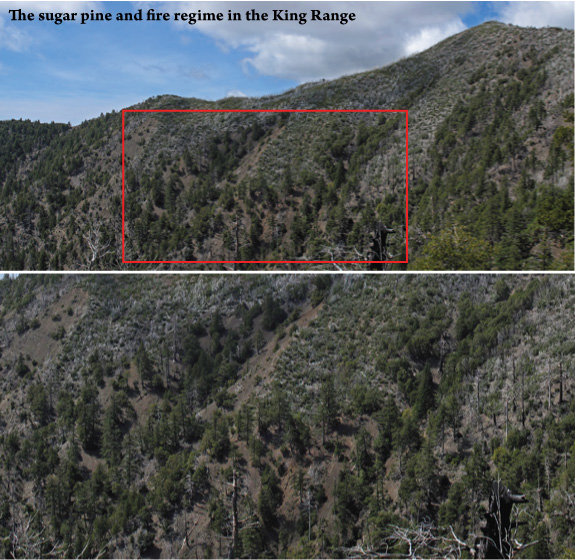

Depending on the slope and aspect of the mountains, as well as where fire was initiated, burn areas blanket almost all hillsides of the King Range. Some fires were mere surface burns while others raged with such intensity as to reach the crowns and scorch entire forested slopes. This melange of severity extremes opens space for some colonizing species or continues to ensure future dominance for the fire adapted ones. Douglas-fir encompasses the epitome of regeneration and endurance within this extreme environment. The landscape tells stories of imperiled survivorship at every turn and Douglas-fir, the most ubiquitous conifer in the West, is at each turn–sharing the story that it is doing just fine in the presence of fire and erosion. But what about the other conifer? Why is it here?

For the first few hours of walking the sugar pine eluded me. However, once I dropped from the summit of King’s Peak and began to walk the ridgelines and stare into the steeply eroded canyons I saw the dangling arms and fresh cones of the King of Pines. John Muir would have been impressed with the fortitude these specimens exhibited–depauperate individuals on denuded hillsides still thriving even though fire had burned all around them. These trees remain in a microsite; now restricted because of Holocene warming. But why have they endured on such restricted sites? What is at work here?

Plant distribution along the Lost Coast is also an ecological study of the balance between rising mountains due to tectonic movement, mountains that then erode almost as fast, and fire. From where I witnessed sugar pine growing, it was as though the two conifers present were not even in competition. Douglas-fir grew everywhere but on the steepest of west and south mountain slopes–where sugar pine became the dominant species. Sugar pines survived here because there were no crown fires. Slopes are so steep that litter can not collect at the bases of the trees–it tumbles down slope. There is therefore nothing to fuel surface fires (much less any ladder fuels to carry fires into the crowns). These trees, not minding these precarious perches, are living the high life.

With any rule, there are usually exceptions. I began to find a few sugar pine mixed with Douglas-fir. In all of these situations Douglas-fir was dominant. It appeared that old-Dougy was tolerant, on occasion, to associating Pinus lamberiana. The question still remains as to why these are the only two conifers in a land (on the regional level) of conifer supremacy. I pose the answer in terms of disturbance–these mountains are disturbed! The majority of the plants here are angiosperms (mostly in the understory) who are able to recolonize quickly after extreme events like fires and landslides. But clearly, the two coniferous exceptions have an ancient mechanism for a less highly derived scheme–take purchase, hold fast, and grow taller than the angiosperm.

These and other botanical secrets can only be understood by spending time in this confounding world we call the Lost Coast–get lost and do some plant exploring.

COMMENT:

AUTHOR: David Fix

DATE: 5/2/2011 4:40:45 PM

I am glad to see Michael’s thoughts here. I, too, was surprised to see Sugar Pine in the King Range, some as near as about one air mile from the ocean. It occurred to me that these trees are not a maritime-air- adapted population; they are actually living ABOVE the fog zone, as most of the fog climbs but halfway up the slopes of King Peak and its neighbors, leaving the upper mountain as if it were farther inland. I had not noticed that there were only two species of conifers. Poor Mike! You must have been casting about for the merest Grand Fir or Incense-cedar seedling…

—–

COMMENT:

AUTHOR: Gambolin’ Man

URL: https://gambolinman.blogspot.com

DATE: 5/2/2011 7:54:38 PM

Great post, nice phyto-detective work, on an elusive area steeped in mystery!