Original Publication DATE: 3/23/2014

Walker Ridge has been on my plant exploration list for many years. I had repeatedly heard about the rare plants, serpentine landscape, and epic wildflower displays that could be found along the ridge and in the adjacent Bear Valley. I also read about a proposal to designate the region as Serpentine National Park which, at the time, was a radical approach to try to halt a major wind turbine project slated for the ridgeline. I was excited to finally explore this place and to locate what has been called the largest stand of McNab cypress in the world. What I found was something entirely different.

The California endemic McNab cypress (Cupressus macnabiana) favors the arid lowlands of the inner Coast Ranges, Sierran foothill woodlands, and chaparral abutting the Central Valley. In this limited distribution, populations are often composed of only a few trees. Like most California cypresses, are believed to have once had a more far-reaching range, but now survive in only fringe habitat. By finding refuge on “edaphic islands” refined adaptations ensure that this habitat (which most other more common plant species find inhospitable) coupled with frequent fire return intervals, promote an environment where seedling recruitment is possible generation after generation.

It is estimated that there are as few as 30 groves of McNab cypress in 12 counties throughout California (Lanner 1999). What these populations have in common is that they always grow on serpentine soil. Along with typical chaparral associates like manzanita and ceanothus, McNab cypress sometimes associates with other conifers including Sargent cypress. In fact, McNab and Sargent cypress are the only California cypresses whose ranges overlap. A good place to see these two together is in the Frenzel Creek Research Natural Area just to the east of Walker Ridge in Colusa County. The extensive serpentine soils found along Walker Ridge have nurtured a once-vast, now recovering, population of this rare conifer for many thousands of years.

What I was able to find on my first visit to Walker Ridge was once the largest stand of McNab cypress I would have ever seen. The vast forest, as recently as spring 2008, would have spread its dwarfed-cypress-wings for several square miles across the southeast flanks of the ridgeline. What I saw were many square miles of burned chaparral with only a few small relic patches of “old-growth” McNab cypress.

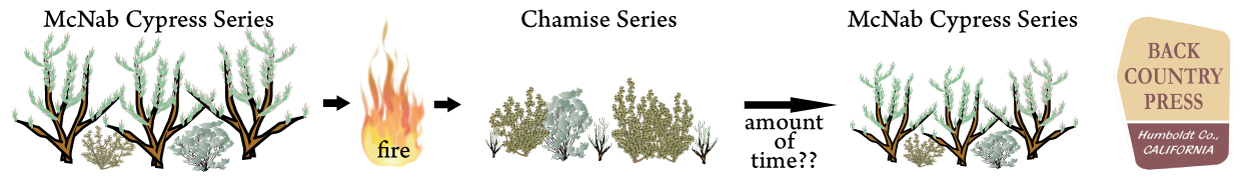

The shift occurred in June 2008 when an off-road enthusiast ignited a fire via metal on serpentine. The amazing result was a “temporary” consummation of this once-vast stand of trees. Six years later this once-largest stand has been reduced to 10-inch tall saplings in a race for space with other fire-dependent chaparral species like manzanita and chamise, and this vegetation shift from McNab cypress to Chamise occurred in mere months. Stand-replacing events such as this are testament to the ecosystem dynamics that can be observed throughout almost all of California’s landscapes and one of the major reasons this is a world biodiversity hotspot.

The questions I had as I drove back to Highway 20 on my way home to Humboldt County was where is the largest stand of McNab cypress now and how many years will it take Walker Ridge’s cypresses to reclaim the title?

Most images were taken along the main road in this area.

Additional resources for Walker Ridge:

- California Native Plant Society Conservation Action

- CNPS, Sacramento Chapter PLANT LIST

- Tuleyome

Citations:

- Lanner, R.M. 1999. Conifers of California. Los Olivos, CA: Cachuma Press.

When you say “Frenzel Creek Research Natural Area just to the east of Walker Ridge in Colusa County” I think you mean to say “Frenzel Creek Research Natural Area just to the north…..”, correct?