Humboldt County, Nevada

When choosing destinations for exploration, isolation has always been an important element in the algorithm. At this point in my Western explorations I’ve been to most mountain ranges in search of solitude and biological uniqueness. So, when the opportunity arose for a fall trip with some college friends, I keyed in on a mountain range I’d never visited mid-way between Arcata, California and Livingston, Montana—deep within Nevada’s High Rock-Black Rock desert.

When dreaming of the desert, I fondly remember visits to southeast Arizona, particularly my first visit to the Chiricahuas. Here, oaks and pines—relicts of the Madro-Teritary Flora—were thriving on the summits of mountains surrounded by the Chihuahuan Desert. In fact, the term “sky island” was originally coined by Weldon Heald in his writings about southeastern Arizona¹. According to McCormack et al. there are 20 sky island complexes around the world, each with a distinct spatial arrangement, age, climate history, and ecological composition. The story of one of these groups of mountains, the Great Basin archipelagos, began with the formation of the nearly 200 mountain ranges over the last 30 million years. As mountains rose, new habitat was formed.

With the onset of Pleistocene cooling 3 million years ago, the planet became wetter as well. Major glaciation and deglaciation events occurred and began to offer conditions for plants and animals to migrate into an area where they were formerly absent. These events were of major importance in the development of the current flora of the Great Basin. During this time, lakes and marshes formed in the lowlands while glaciers scoured the highest peaks. The current ecology of the region is due, in large part, to this cooling period as it allowed species that had not been in the region before to establish and colonize.

Pleistocene colonization ended with Holocene warming. Over the last 11,000 years many of these Pleistocene “invaders” went extinct while others are now biogeographically isolated where, for example, water remains in the lowlands or mountain geography offers a high elevation climate similar to that of the Pleistocene. The current composition of the Great Basin Archipelagos is, interestingly, largely governed by extinction events as the climate has warmed. The places were Pleistocene relicts remain are harbingers for our current climate changes and thus, highly interesting for anyone interested in biogeography and evolution. Just like an ocean would act like a barrier for water-bound islands, the low-elevation desert habitat now acts as a barrier for dispersal form these sky islands.

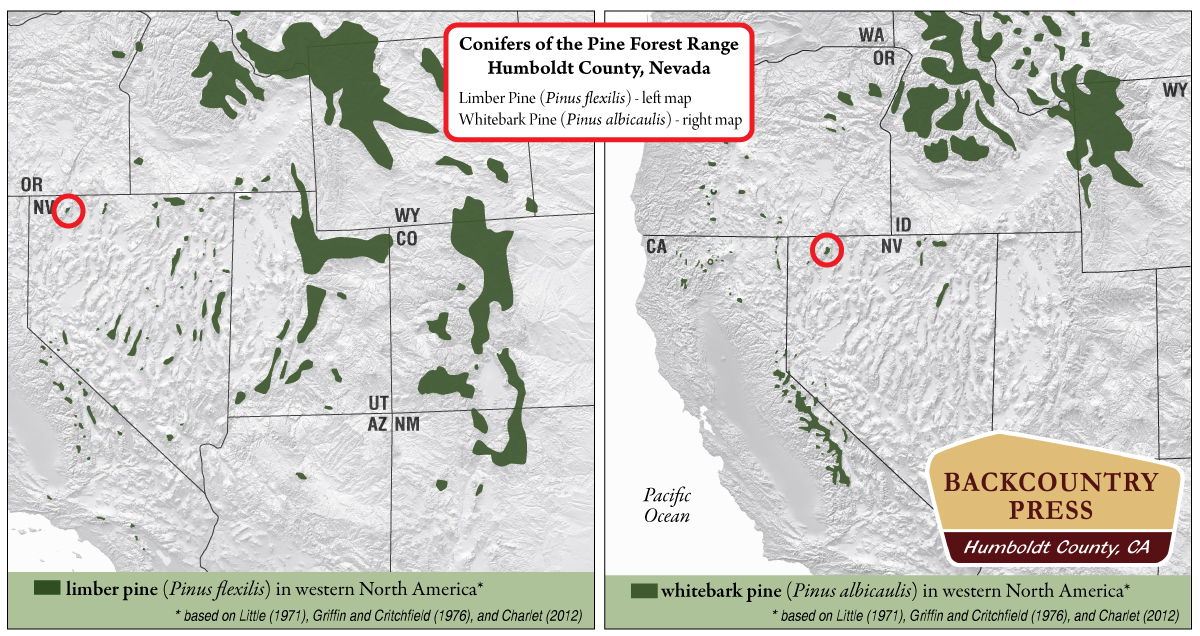

As a bonus for me (and other cone-heads), the highest peaks across the Great Basin hold relict stands of conifers. The Pine Forest Range harbors two species of conifers above 7,500’—limber pine (Pinus flexilis) and whitebark pine (Pinus albicaulis). What follows is a photographic journey into one of the most isolated high elevation Great Basin archipelagos.

Pine Forest Range – whitebark pine field notes from October 13th-14th, 2014:

- Whitebark pine stands are healthy, with only 5-10% mortality from Mountain Pine Beetles, exclusively on north-northwest facing slopes. There are active infestation sites where small numbers of trees (5-10 per site) were killed this year.

- There is extensive evidence of fire <8,500′ – I doubt this range has ever been managed when a fire was started by lightening.

- I only saw 4 Clark’s nutcrackers the entire time.

- Whitebark pine are pioneering new habitat in this region, moving downslope into meadow systems. This is also happening “nearby” in the Warner Mountains.

- Common associates include Limber pine (Pinus flexilis) [right around the 8,000′ level but rarely above or below], Curlleaf mountain mahogany (Cercocarpus ledifolius), Quaking aspen (Populus tremuloides), Ribes spp., Artemesia spp.

- Find the Pine Forest Range on Google Maps.

References:

- McCormack, J., H. Huang, L. Knowles. 2009. Sky Islands. University of Michigan.

Resources:

- Great Basin – Mojave Desert by the USGS

- Basin and Range – National Park Service

Interesting explorations. Any evidence of other relic species or new species invading these mtn island habitats -such possibly as Abies sp?

Mike- We did not see any other conifers, but Abies concolor are “relatively” close in both the Warner Mtns. and Steens Mtns., so maybe!

David Charlet has a brief description of the Pine Forest Range in his new book “Nevada Mountains: Landforms, Trees, and Vegetation”.

Thanks Doug, I have to get that book! David was a big help when I was writing Conifers of the Pacific Slope.

Yep…it’s well done. Maps, graphics and layout are great. Pictures are very well done. Ranks up there as one of the best plant atlases I’ve seen produced in recent times. Perhaps a little large for a “stocking stuffer”, but I’d put it on my Christmas list!

Hi Michael,

I am curious if you saw any evidence of blue (dusky/sooty) grouse in the Pine Forest range. They are not reported to be present in Steen’s Mtn, another isolated massif/range in the area but as I have seen them there, I know that information is limited. The habitat in the Pine Forest Range would appear to be ideal for blue grouse but as any population would likely be isolated from other habitats they might be fragile.

regards

Andy Peterson

Andy- thanks for the comment. I almost always keep a bird list on wilderness area backpacking trips but I checked my journal and did not on this trip. Not sure why other than it was a quick one. I do not remember grouse. Sorry! But I’d love to go back and if I do…