How do you go about choosing a hike?

I have used various approaches which always involve careful map study, perusing the pages of hiking guides, and most importantly for me—studying field guides. As I get older, choosing a hiking destination is becoming more critical, with so much to see and even more to learn.

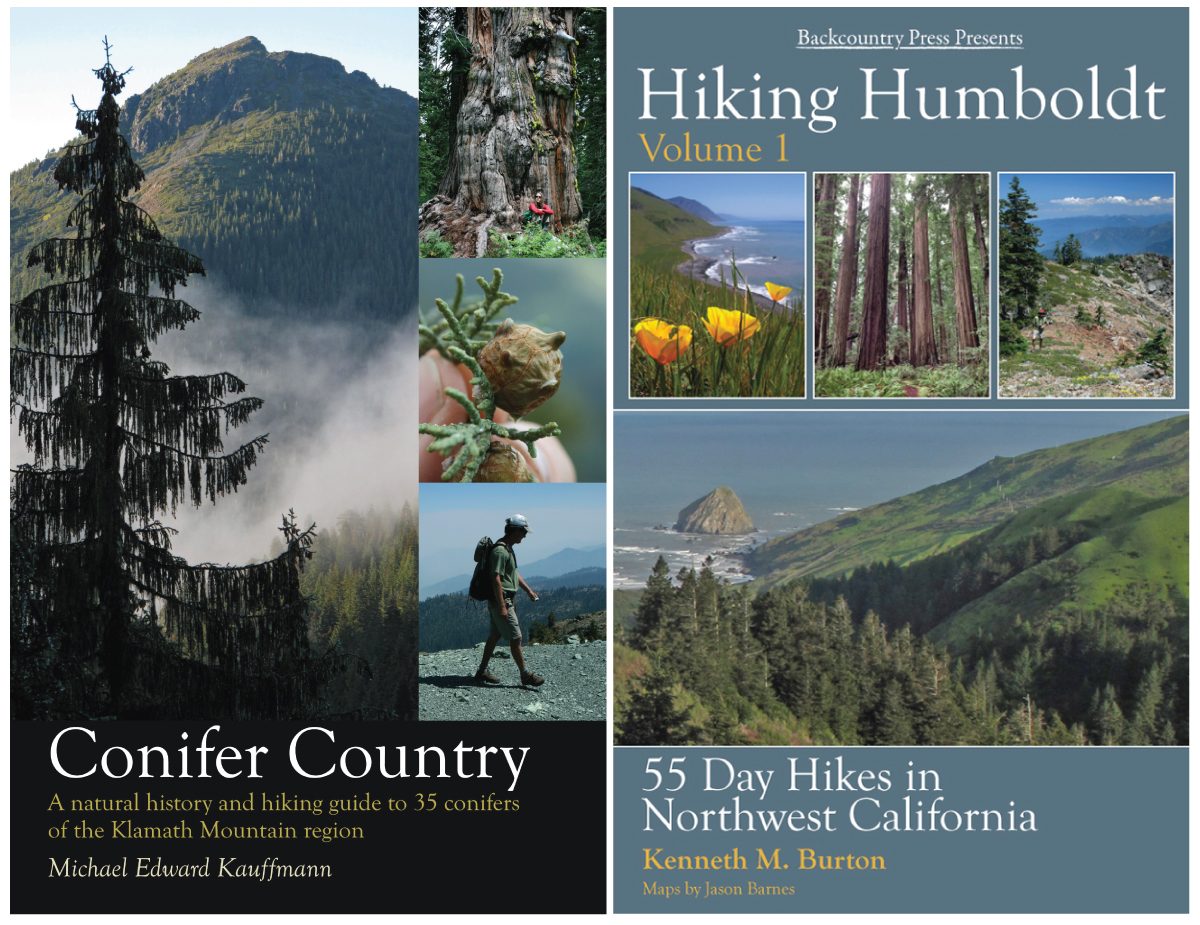

Over time, I have gone about choosing a hike based more as a destination for discovery before any other factor. I think I first caught the hiking-for-natural-discovery bug while selecting a backpacking route exclusively to see condors in the Sespe Wilderness of southern California. When I moved to Humboldt in 2002, I graduated from bird destinations to plant exploring as I began searching out rare and unusual conifer species in our local mountains. This regular wilderness sideline blossomed into a Master’s Degree from Humboldt State University when I published my first book Conifer Country: A natural history and hiking guide to the conifers of northwest California in 2012. For 10 years I hiked to find and understand trees. These trees, and the places they grow, helped me develop a deeper passion for place and an understanding of the unique natural history of northwest California.

Why did I become obsessed with conifers? In my opinion, this ancient tree lineage—think evolution before the dinosaurs—is the most magical on Earth. For more details about this marvelous group of plants check out my books, but the gist of my conifer obsession is centered around their survival strategy. In most cases conifers grow where other plants cannot—including the highest peaks and most rugged landscapes in the West. These are places which today mimic ancient climates and environments when conifers were much more common across the planet. These magical locations are also the destinations we often choose for summer hiking destinations, after the snow melts.

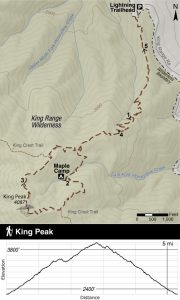

Over thousands of miles on trail I have had plenty of time to think as I walk. This mindfulness first developed my senses, then connected me to nature, and eventually honed my observations skills. Now, when walking the western landscape I know where to expect various plants and animals depending on longitude, latitude, elevation, and habitat. In this way, the predictability of the natural world—coupled with a fine walk—is my therapy. A hike to King Peak in southern Humboldt County offered me one such therapeutic destination—chosen at first glance for the epic views but upon further consideration for its unusual plants and animals associations.

Hiking to King Peak

The King Range is part of the greater North Coast Range, which extends north from San Francisco and tapers to a sliver, pinched against the Pacific Ocean by the Klamath Mountains, in northern Humboldt County. The Lost Coast presents assemblages of plant (known as associations) that have puzzled botanists for years. For instance, unlike the more arid Santa Lucia Mountains of central California—which hold canyons lined with redwoods (Sequoia sempervirens)—redwood do not grow in the King Range.

Humboldt Bay is at the southern tip of the greatest temperate coniferous rainforests on Earth. In coastal Del Norte County northward rain falls at a rate of 100 inches per year. South of Ferndale in the King Range rains falls at a similar rate but conifers common further north in the temperate rainforest, like Sitka spruce (Picea sitchensis), western hemlock (Tsuga heterophylla), and western redcedar (Thuja plicata) are also absent in the King Range. Why do these botanical anomalies occur when the climate should offer these plants a chance to survive?

While reasons are wide-ranging, discoveries can be found along the trail to King Peak that can lead to understandings about these botanical anomalies. Climbing from the Lightning Trailhead, at the end of King Range Road, the route ambles gently at first, and soon with switchbacks, through a forest that holds both large, healthy trees and depauperate bushes with scraggly burnt branches. It is a landscape of juxtaposition.

The King Range is extremely steep, with slopes in many canyons greater than 50 degrees. Torrential rains fall here in the winter, then hardly at all in the summer. Plant communities here, ranging from forest to chaparral to coastal scrub, show signs of the frequent occurrence of fire while other pockets—usually steep forested slopes—have not burned for centuries. It is a land that is predictably unpredictable, full of question and hidden answers.

Flora and Fauna of King Peak

Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii), the most common conifer species in western North America, is the omnipresent tree on this hike and across the King Range. Its ubiquitous nature and economic value define it as the West’s all-purpose tree. The species achieves tremendous size in the Pacific Northwest and historical data from the early twentieth century recorded heights of 393’ and estimated volumes exceeding 17,000 ft³. If true, the species was once both taller than redwoods! and larger than giant sequoias (this statement was determined to be incorrect and deleted after publishing). There are some big Douglas-firs in the King Range, but generally their prolific survival here speaks to the versatility of the species and its adaptability to the cruel wind-swept and fire scarred landscape.

Sugar pines survive in small stands in the King Range as relicts from a time when the climate was different than today.

While Douglas-firs are a common conifer on the hike to King Peak, sugar pines (Pinus lambertiana) are uncommon. The groves that now survive here, after thousands of years of climatic changes—many mountain ridges and river canyons from other sugar pine relatives—hints at a bygone time when the King Range was quite a different place. Why are sugar pines in the King Range? The steepest slopes offer a refuge, mimicking an environment when the climate was colder and wetter. These slopes are so steep that the frequent fires of the region cannot, and have not, spread into the sugar pine groves. These inhabited slopes are so steep that understory litter does not collect, instead cascading down the mountain. Without understory fuel, fire typically does not spread into these pine groves.

Tens of millions of years ago pines evolved in the subtropics and about 15 million years ago so did California’s iconic manzanitas. The rock stars of woody shrubs in California also survive in the King Range. Near the summit of King Peak, Eastwood’s Manzanita (Arctostaphylos glandulosa) finds subtropical habitat—at the edge of the rainforest—along fire-scorched ridgelines. Manzanitas are fire-adapted and typify the chaparral of central and southern California. Coastal chaparral becomes less common in northern California. In the King Range, and a few other outlying coastal regions of the far-north, chaparral defines an increasingly rare habitat that evolved with summer drought and frequent fire.

Plants migrate slowly across the landscape, taking thousands of years to pioneer new habitats by crossing mountain ridges and river valleys with a variety seed-dispersal mechanisms. These are distances birds can travel in a matter of minutes. The unusual California thrasher (Toxostoma redivivum) is a more mobile component of the King Range. Here, at the northern extent of its range, the clandestine thrashers survive here in the coastal chaparral where they find food and nesting habitat in the shrubby understory. Avid birders across the county make pilgrimages here to check the California thrasher off their county list while simultaneously enjoying a hike in the King Range Wilderness.

How do you choose a hike? If I might suggest several ways…Conifer Country offers 27 hikes that will feed your botanical desires across the Coast Range and Klamath Mountains and send you on a scavenger-hike for trees. The newly released Hiking Humboldt Volume 1 suggests 55 day hikes that are accompanied by bird lists for each hike on the companion website, composed by the author Ken Burton. Whatever you choose, get outside and enjoy what our natural wonders have to share.

Hello Michael:

Thank you for your blogs–I look forward to reading them and enjoying the beauty of nature, and conifers in particular.

Just below the heading Flora and Fauna of King Peak you state that from historical records there were Douglas Fir Trees that were taller than Coastal Redwoods and “larger than Giant Sequoias”. I am vaguely familiar with the historical records of taller than redwood Douglas Firs, but Firs larger than Giant Sequoias is new to me. Please provide information to help me obtain a better understanding of this phenomenon.

Perhaps a blog on historically giant Douglas Firs would prove interesting to folks.

Have been using the Field Guide to Manzanitas to explore this large genus. Thanks a million for publishing this book.

Hi Brian- Thanks for the note and for supporting my books. This information, cited in Conifer Country’s write-up of the Douglas-fir, is from Bob Van Pelt’s 1991 book (https://www.amazon.com/Forest-Giants-Pacific-Coast-Robert/dp/0295981407). It looks like the statement about volume larger than a giant sequoia is no longer correct with the current measuring techniques but was when only DBH, height, and crown-spread were used to measure trees. General Sherman has now been determined to have a volume over 50,000 cubic feet. The estimate for PSME is nowhere near that. Thanks for catching that error! But the height could have indeed been taller than redwoods.

Michael, thanks for the King Range writeup. I spent a summer and fall in that special, unusual place in 1977 as a frontcountry recreation contact and backcountry ranger, during the great drought of that time. Hope those few lovely springs in the higher country haven’t dried up and gone away in the years since. The, um, notable agricultural industry was already in full swing on the east side of the range back then! (I also remember lots of rattlers and tanoaks, which I read now have been ‘re-genused’.)

Dean- thanks for sharing your memories and for following the blog. It is a lovely and wild place for sure.