Channel Islands National Park

In 1998 I first visited the Channel Islands. This was early in my naturalist career but I was struck, none-the-less, by the beauty and isolation I found on Santa Cruz Island. On that trip I first saw the endemic island scrub jay (Aphelocoma insularis) and began to develop an understanding and interest in island biogeography. Twenty years later this experience brought me to Santa Rosa Island–in major part to see the Torrey pine grove–but also for the opportunity to explore one of the least visited places in Southern California.

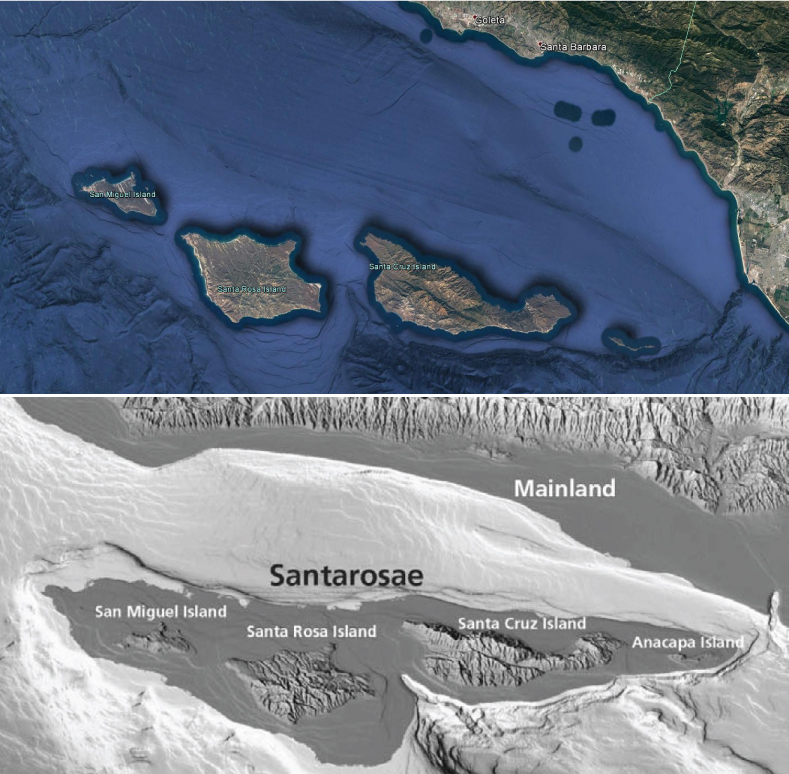

Santa Rosa Island is separated from the mainland by over 25 miles of water. The next closest landmass is San Miguel, which is now isolated from Santa Rosa by three miles of water. Isolation has nurtured endemism on both a localized island level as well as on a unifying level between islands. Combined, all the Channel Islands are home to 150 species of unique plants and animals. Santa Rosa hosts 46 of those, including six endemic plants that grow nowhere else.

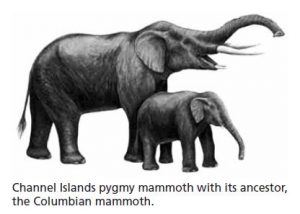

Ecological processes on islands often act differently that on larger land masses. One particular phenomenon I have always found interesting is insular dwarfism. This evolutionary process selects for size reduction in animals over many generations. When a population’s range is limited by unsuitable habitat, food availability may occasionally decline with climatic fluctuations. It is proposed that insular dwarfism is naturally selected for because smaller animals more easily survive caloric fluctuation–needing less food for survival. This phenomenon is witnessed on the Channel Islands in several instances including the now extinct pygmy mammoths as well as in the extant island foxes (see below).

Ecologists define insular environments (islands in this case) as habitats suitable for a specific ecosystem (land), surrounded by an expanse of unsuitable habitat (ocean). On undisturbed islands, biodiversity is a balance between immigration, speciation, and extinction– wherein extinctions are generally affected by the availability of suitable habitat. The Channel Islands have seen their fair share of extinctions–both across deep and recent times.

At the end of the Pleistocene, as sea levels rose and the planet warmed, the surface area of Santarosae Island shrank and the four highest land masses became the islands we know today (see image above). With the loss of habitat, species settled into new environments that mimicked those in which they had previously evolved within or adapted to new environments (and thus speciated). With the arrival of humans, more species became extinct with pressure from Native American hunting (bye bye mammoths) and later introduced species like elk, deer, pigs, and cows.

Today, 25 percent of the plants that call Santa Rosa home are non-native. That sounds bad, but there has been an amazing recent recovery witnessed. Due to the efforts of conservationists from agencies like the Nature Conservancy, USGS, and National Park Service the island are healing from centuries of poor stewardship. There are numerous stories that exemplify these efforts but, as far as the plants go, the most important for Santa Rosa was the removal of the herbivorous megafauna like deer, elk, pigs, and cows.

Pigs were first introduced on Santa Rosa in the mid 1800s. By 1888 it is estimated, based on historical records, that there were only 100 Torrey pines on the island. Today, all herbivorous megafauna have been removed (minus 5 sterile horses from the old ranch) and the Torrey pine are thriving–with an estimated 12,300 trees–one-quarter of which are saplings!

The poster-child for recovery is the island fox (Urocyon littoralis) which lives on six of the eight Channel Islands—San Miguel, Santa Rosa, Santa Cruz, Santa Catalina, San Nicolas, and San Clemente. While 20 percent smaller than its gray fox (Urocyon cinereoargenteus) relative on the mainland (insular dwarfism!) it is the largest native mammal on the islands at the size of a house cat. This diurnal predator has lived on the islands for at least 6,000 years, based on carbon dating of remains, and probably arrived by “rafting” to Santarosae when the channel was more narrow. Beginning in the mid-90s, populations began to decline due to predation from non-native golden eagles that arrived on the scene. Humans intervened by removing the eagles when the fox hit the endangered species list and, today, the populations have rebounded and foxes are thriving.

All the scientists I spoke with during this trip had the same message–the islands are recovering better than they ever could have ever imagined. The last deer were removed from Santa Rosa Island only six years ago and the reponse by various species has been quite noticeable. This is includes one plant that was almost listed as an endangered species–the Santa Rosa Island manzanita (Arctostaphylos confertiflora). Without browsing pressure, plants like the manzanita are finally able to grow new leaves, increase photosynthetic levels, and grow normally.

Plan a visit to one of the gems of Southern California, experience its recoveries, endemism, and ecology–including rejuvenation and renewal on many levels.

Resources

- Santa Rosa Island Plant list I generated from CalFlora

- Channel Island Bird List

- Santa Rosa Island Interpretive Guide

- Hiking Santa Rosa Island

- eBird list from my trip

Other posts about Santa Rosa Island