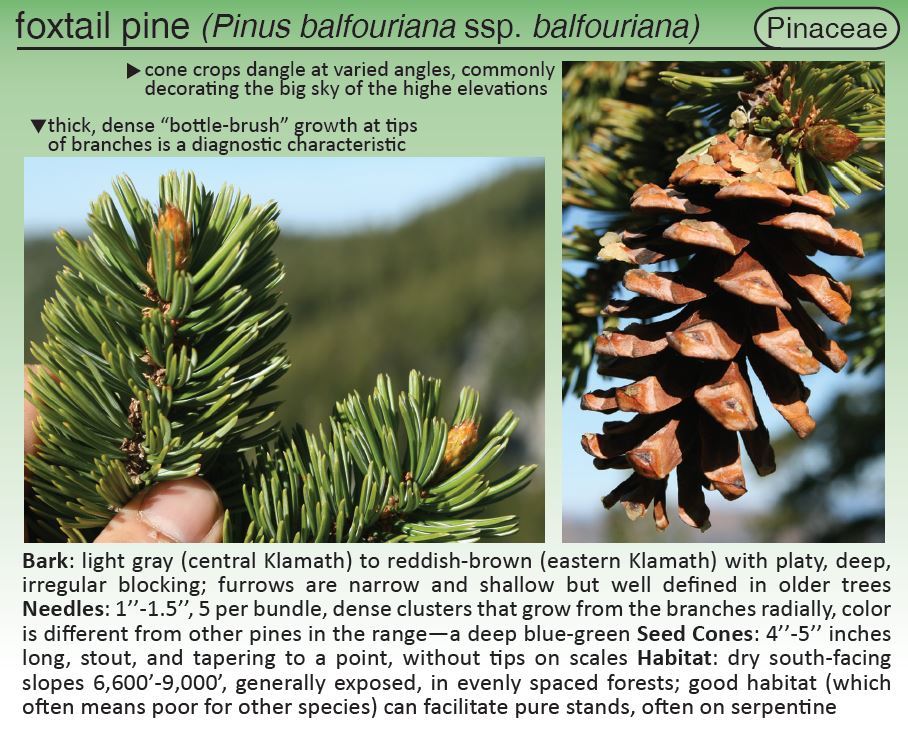

Pinus balfouriana ssp. balfouriana

“Whether old or young, sheltered or exposed to the wildest of gales, this tree is ever found irrepressibly and extravagantly picturesque and offers a richer and more varied series of forms to the artist than any other conifer I know of.”

−John Muir

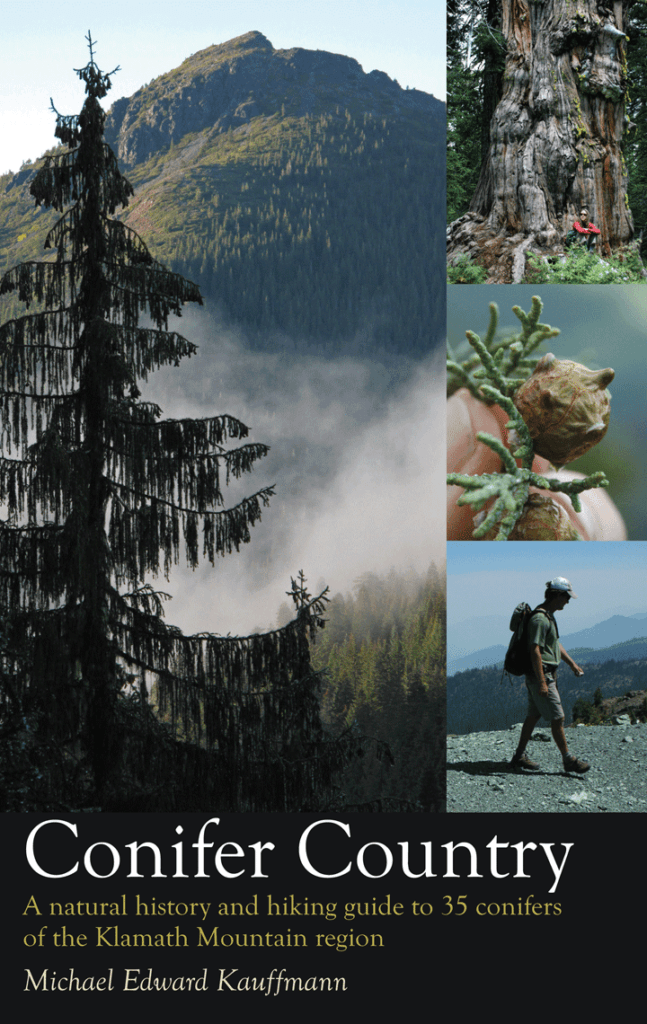

The following excerpt is from my book Conifer Country. I was inspired to publish it here after a recent trip with my son to visit and measure the Klamath Mountain champion foxtail pine. After this trip, the foxtail pine is his favorite tree species too 🙂

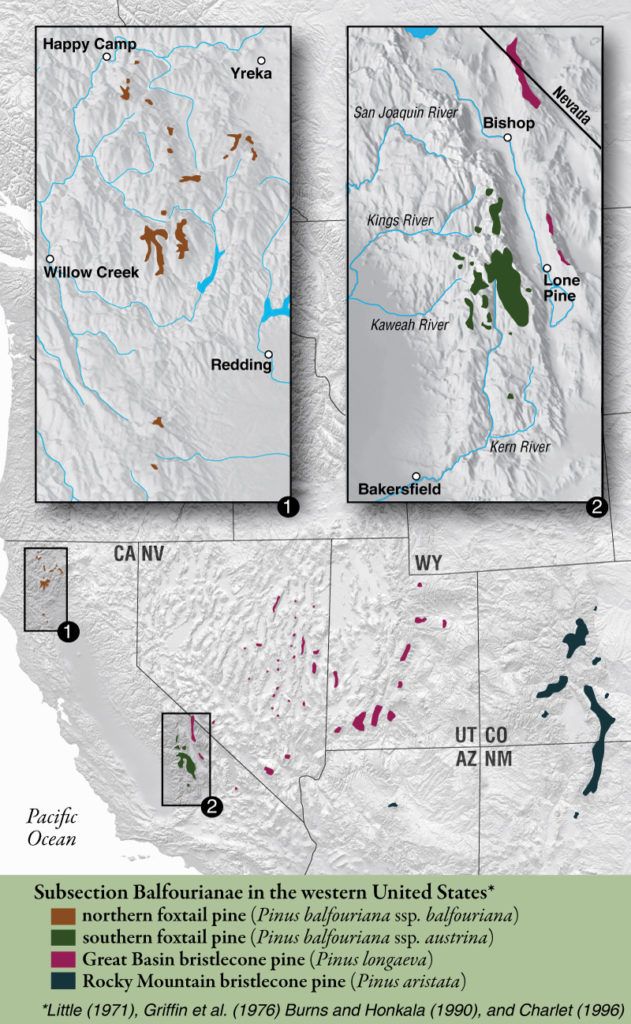

California’s endemic foxtail pines have established two esoteric populations abscinded by nearly 500 miles of rolling mountains and deep valleys. The species was first described by John Jeffrey near Mount Shasta in 1852 , which was most likely a population near Mount Eddy or in the Scott Mountains. Later, this species was discovered in the high elevations (9,000’-12,000’) of the southern Sierra Nevada. The ecological context of Klamath foxtail pines in the Klamath Mountains differs drastically from that in the Sierra Nevada due to the divergence of these populations in the mid-Pleistocene. Though separated over one million years ago, both subspecies exhibit a radiance and individuality for which I honor them as my favorite conifer.

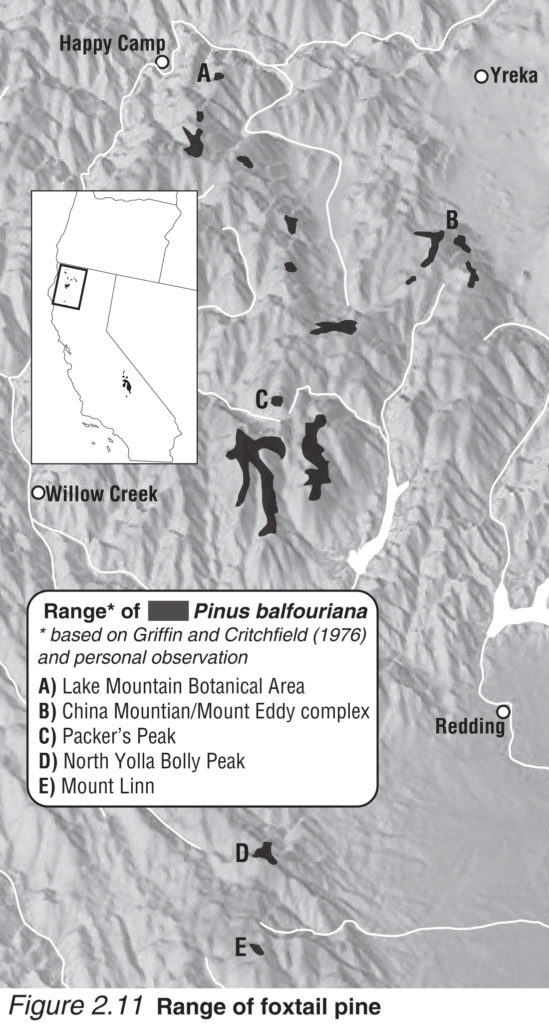

With separation in space and time, divergence—including cone orientation, seed character, crown form, foliage, and even chemistry—has occurred between the two subspecies. Another reason for these variations are genetic bottlenecks that have been promulgated by spatially restricted microsite adaptations, particularly in the Klamath Mountains . Northern foxtail pines (var. balfouriana) are isolated on sky islands—local mountain tops and ridgelines—from 6,500’ to 9,000’ in the eastern half of the Klamath Mountains. By my count there are 16 isolated sub-populations each consisting of one to several isolated mountain-top populations, except in the Trinity Alps where they are locally common in the more contiguous high elevations. On these sites, proper geologic, topographic, and climatic conditions have offered synergistic alliances with shade-tolerant and faster-growing firs and hemlocks.

Klamath foxtail pines grow on two distinct substrates, each exhibiting discrete forest associations. Most stands are on serpentine soils with a south or southwest-facing aspect (shade-tolerant fir and hemlock exist on cooler north-facing slopes). Foxtail pine does surprisingly well on nutrient-deficient soils as long as light is not limiting. A more complex and unusual survival regime occurs on granitic glacial moraines of the Salmon Mountains. Here, on south and southeast-facing slopes, foxtail pine survives with decreased competition because large boulder fields spatially restrict other trees from growing near them and thus “stealing sunlight.”

Klamath Mountain trees associate with up to nine other conifers: incense-cedar, Brewer spruce, western white pine, whitebark pine, Jeffrey pine, mountain hemlock, Shasta fir, white fir, and Douglas-fir. In the Sierra their only associates are red fir, whitebark pine, lodgepole pine and, in one instance, limber pine. Having enjoyed many subalpine populations of foxtail pines in the Sierra Nevada before venturing to the Klamath Mountains, I was astonished to see Jeffrey pines and incense-cedars touching roots with foxtails. Southern foxtail pine form pure stands of many square miles (e.g., the headwaters of the Kern River in Sequoia National Park). These groves are picturesquely spaced at timberline on metamorphic and igneous rock.

In groves of Klamath foxtail pine, individuals are denser per unit area than in the Sierra Nevada, probably due to harmonious interactions with numerous conifers. Flat-top crowns are common on trees in the region because of the denser groves. This bauplän (growth form) allows trees to more efficiently capture light. In order for these trees to differentiate and ultimately form this unique crown structure, they compensate by reducing their trunk diameter in favor of increased height and longer-term retention of foliage. The point is to maximize light consumption, which is a critical adaptation for a shade-intolerant species.

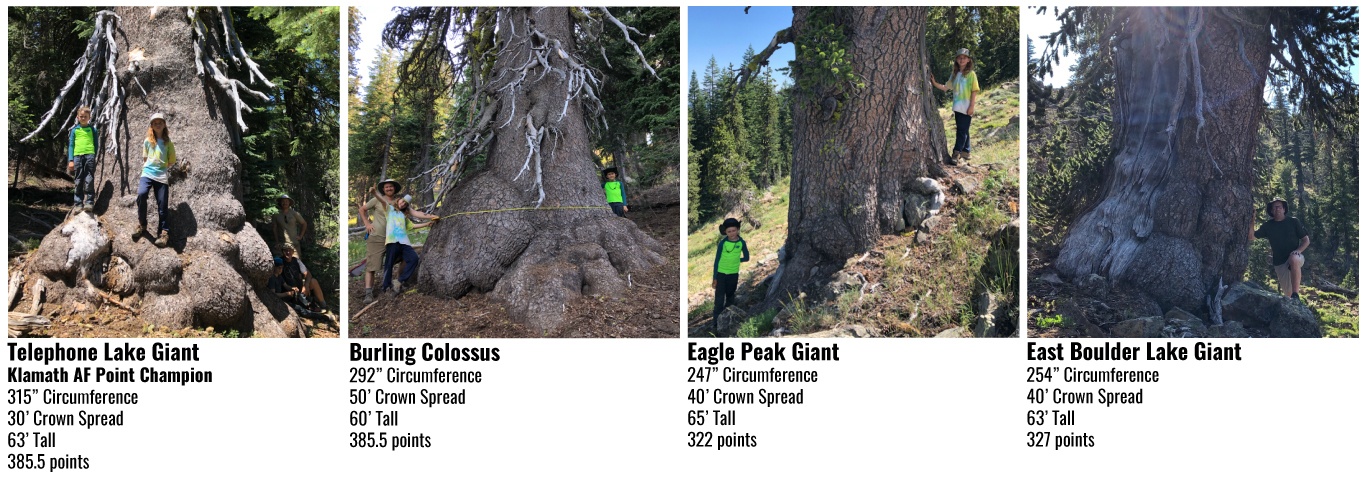

Another difference between these two populations is their bark. Northern trees have gray to light brown bark that forms narrow ridges between square blocking patterns, while southern trees have reddish bark that forms deeper furrows and more distinct blocking patterns. Both populations maintain the distinct “bottle-brush tassle” needle growth described by John Muir, but branches tend to sweep upward in the Sierra and downward or outward in the Klamath. Trees in the Klamath grow taller than southern trees. Though foxtail pines can attain large size in the Klamath, they are on average smaller than the southern foxtail pine trees. This is most likely because they do not reach as old an age. While the southern trees are for the most part faster growing and longer-lived than the northern trees, several of the world’s largest discovered foxtail pines are in the Trinity Alps, in a south-facing, serpentine soil, spring-fed canyons along the Pacific Crest Trail.

I find that the high, dry ridgelines of the Klamath, to which foxtail pine is restricted, offer the most spectacular scenery in the region. These localities are difficult to reach, often requiring a hike of several miles. One of the only populations that can be reached by car is in the Lake Mountain Botanical Area, southeast of Seiad Valley. This, the northernmost population, is adorned by an active fire lookout high above the Klamath and Scott rivers with views into Oregon. One can also drive to within a short hike of foxtail pines below China Mountain (on a difficult logging road) in the Klamath National Forest. In the Yolla Bolly-Middle Eel Wilderness and on Mount Eddy, foxtail pines form almost pure stands but are a day’s hike from the roads.

Like other species in a subsection known as Balfourianae (P. balfouriana, P. longaeva, and P. aristata), foxtail pines arise from ancient stock. Some 46-million-year-old fossils attributed to Pinus balfouroides have been found near Thunder Mountain, Idaho. Fossils from Pinus crossii, which is similar to other bristlecone species, has been found in Nevada, New Mexico, and Colorado and dated to 42 Ma, 32 Ma, and 27 Ma, respectively. Throughout the 40+ million years of evolution across western North America, these species have repeatedly expanded their range down-slope or into lower latitudes in cool glacial periods and upslope or into the northern latitudes in warmer times. For example, remains of a foxtail pine cone was discovered near Clear Lake, California , which is 5,000’ lower in elevation than where they are found today in northwest California.

Distinct similarities exist between the two bristlecone pine species of the Great Basin (Pinus longaeva) and Rocky Mountains (Pinus aristata) and the foxtail pine of the Sierra Nevada and Klamath Mountains. Separated and isolated by spreading mountains and climatic change over millions of years, these trees have evolved into three separate species. All three, coupled with where they grow, create some of the West’s most spectacular scenery. On trips to Great Basin National Park in Nevada or the San Francisco Peaks in Arizona one can enjoy the bristlecone pines. I consider the bristlecone and foxtail pines the crowning jewels of the coniferous inter-mountain West.

Thank you for those amazing photos of Foxtail Pines! And thanks for introducing me to the species. I agree, it is a cool conifer! Thanks so much for all your research and enthusiasm! I appreciate your love of trees.

Thanks for the kind words and comment Christine. I think these trees in particular are easy to love!