I am proud to say that the San Francisco Chronicle has listed The Klamath Mountains: A Natural History as one of the best nonfiction books of 2022!

Allison Poklemba cooked up a trailer about the book, I think she did a great job 😉

Educator • Author • Ecologist

I am proud to say that the San Francisco Chronicle has listed The Klamath Mountains: A Natural History as one of the best nonfiction books of 2022!

Allison Poklemba cooked up a trailer about the book, I think she did a great job 😉

I could not be more proud of our new book. It is, in reality, a project 10-years in the making. I first started cooking up the idea when I finished Conifer Country in 2012 based on the fact that a natural history had never been written for the Klamath Mountains. Around 2015, during a winter gathering, I proposed an outline to a group of friends and asked who wanted to help write the book with me. Justin Garwood raised his hand and the rest is now history!

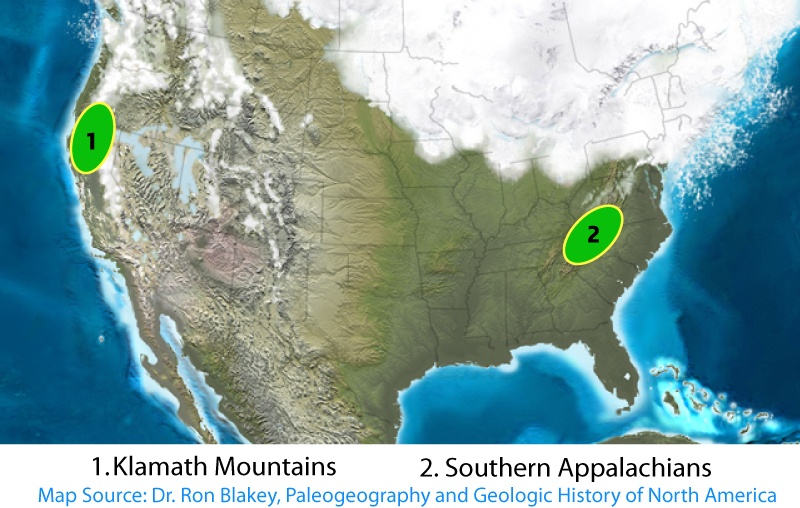

Continue reading “The Klamath Mountains: A Natural History”In the Tertiary, beginning around 65 million years ago [Ma], a temperate forest prevailed unlike any other in Earth’s history. Referred to as the Arcto-Tertiary forest—existing on a landmass that would soon become North America, Europe, and Asia—a blending of conifers and broad-leaved trees dominated the landscape. With continental drift and climate change, the offspring of these great forests were fragmented. Over time, ice ages came and went, causing a change in flora as increasingly dry conditions became more common. The descendants of the Arcto-Tertiary forest became less extensive and more isolated. These progenitors have remained, finding refuge in the higher and cooler regions which maintained a climate more similar to that of the early Tertiary and creating, today, a strong Klamath-Appalachian Connection (see R. H. Whittaker 1961).

On our summer vacation, we visited one of two remaining old-growth tracts in South Carolina. Based on what remains–a small legacy indeed–it is arguably the best and largest example of an old-growth bald cypress forest left in the world. The protected land consists of over 18,000 acres of mainly bald cypress and tupelo gum hardwood forest and swamp with approximately 1,800 acres of old-growth.

Continue reading “Francis Beidler Forest”California’s deserts have always fascinated me. In the late 1990s and early 2000s I visited many areas of the Sonoran, Mojave, and Great Basin in California while teaching in Southern California. Since moving north, I have often dreamed of returning. In 2020 Backcountry Press was approached by Dr. Philip Rundel from UCLA about doing a book on California Desert Plants. This was an exciting prospect and an easy decision to make. After over a year of work (he has been working on the idea on and off for 15 years) we are excited to announce that the book is done.

For me, this book is amazing because it tells the story of one of the harshest environments on Earth. There are three distinct desert areas in California—the northwestern portion of the larger Sonoran Desert, the Mojave Desert which extends beyond the state, and the western margin of the Great Basin. A key feature of the California deserts is the dominance of infrequent rainfall in the cool winter months and general absence of rainfall and associated drought in the summer months when warm temperatures are otherwise favorable for growth. The combination of these harsh conditions nurture amazing plants with a complicated variety of adaptations.

If you love the California deserts and its plants, and would like to help support this passion project head on over to Backcountry Press and pick up a copy today.

Continue reading “California Desert Plants”