Exploring the Mojave National Preserve

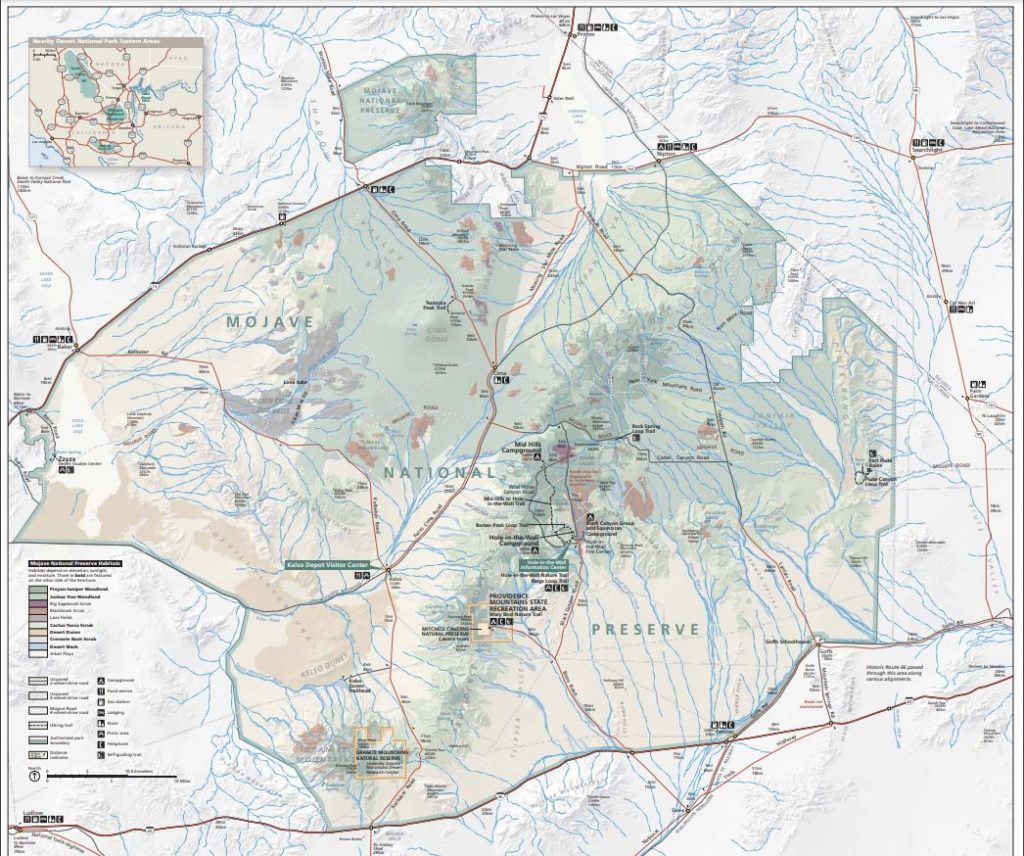

Established in 1994, the Mojave National Preserve encompasses 1.6 million acres roughly bounded by Interstates 15 and 40. Most simply pass by this region on their way to other places (Lost Wages, Nevada for example) but it is a premier desert park. This vast and varied landscape includes dunes, dry lakebeds, granites, volcanics (domes, lava flows, and cinder cones), limestones, and sedimentary deposits which support a diverse collection of plants. The preserve includes creosote bush lowlands at 880 feet near Baker all the way up to conifer woodlands at 7,929 feet on the summit of Clark Mountain. The Mojave Wilderness is 700,000 acres of the preserve.

Within the preserve is the University of California Riverside’s Sweeney Granite Mountains Desert Research Center. The University of California’s GMDRC is dedicated to academic research and teaching and access is solely through an application approval process. This was was our basecamp. I am working on a book with Philip Rundel and Bob Patterson called California Desert Plants (Backcountry Press, late 2022) so we came to experience, explore, photograph, and write about the regional wonders. In particular, we wanted to find trees in the desert.