A note for you, lover of conifers

A few years after the first edition was first published, I was deep in the Siskiyou Wilderness in search of yellow-cedar stands. To my surprise another backpacker came stumbling through the brush. After we said hello, he got a smile on his face as he pulled a copy of Conifer Country from his backpack and asked for an autograph. My heart swelled with joy as we discussed how to tell the difference between yellow-cedar and Port Orford-cedar with both the book and plants in hand. This experience was grounding and simply lovely.

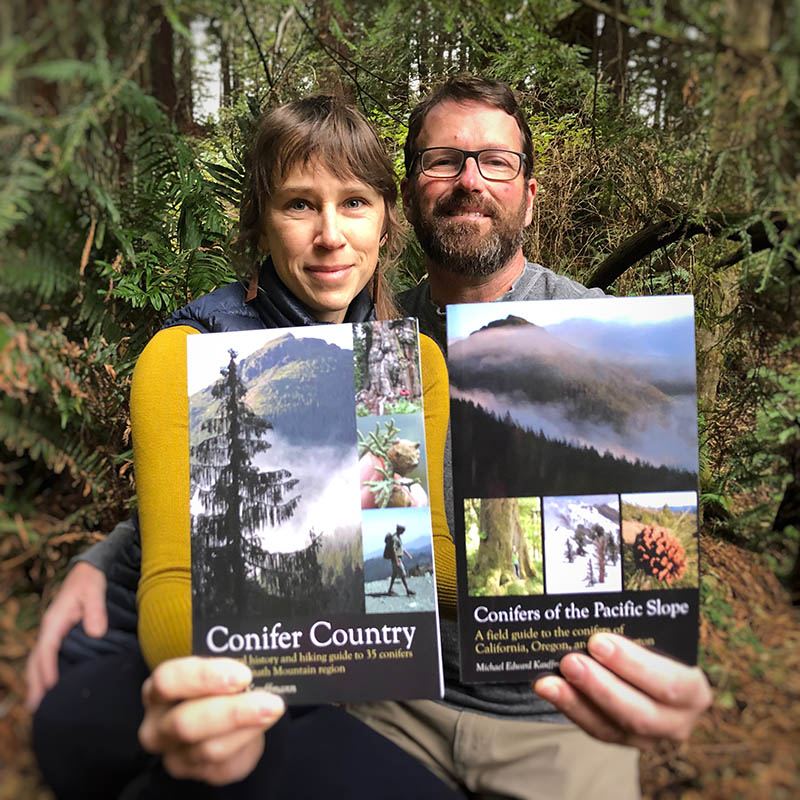

It has been 12 years since Backcountry Press first published this book. My wife Allison and I launched the business to support that publication. We took this risk to tell the story of science in interesting and engaging ways–to inspire deeper connections to the Earth. Looking back, I am amazed at what this project has brought us and the connections it has helped establish with the land and its enlightened people.