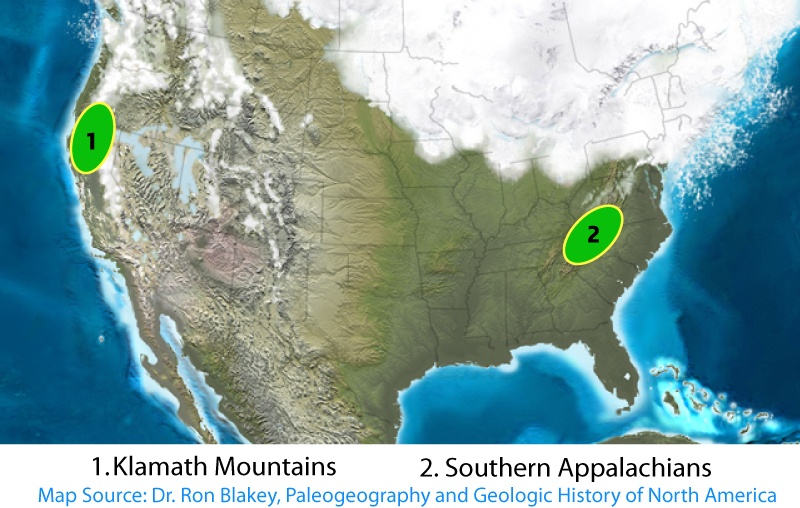

In the Tertiary, beginning around 65 million years ago [Ma], a temperate forest prevailed unlike any other in Earth’s history. Referred to as the Arcto-Tertiary forest—existing on a landmass that would soon become North America, Europe, and Asia—a blending of conifers and broad-leaved trees dominated the landscape. With continental drift and climate change, the offspring of these great forests were fragmented. Over time, ice ages came and went, causing a change in flora as increasingly dry conditions became more common. The descendants of the Arcto-Tertiary forest became less extensive and more isolated. These progenitors have remained, finding refuge in the higher and cooler regions which maintained a climate more similar to that of the early Tertiary and creating, today, a strong Klamath-Appalachian Connection (see R. H. Whittaker 1961).