Original Publication DATE: 3/17/2010

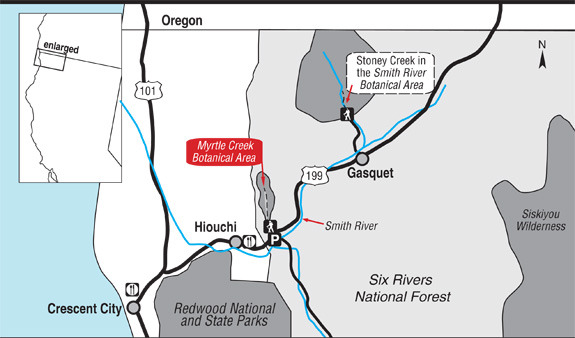

Situated on the border of two major rock types, Myrtle Creek Botanical Area is floristically challenging as well as aesthetically arousing due to this unique geological architecture. Along the western slopes of the Myrtle Creek drainage, the North Coast Range meets the Klamath Mountains against an ancient island-arc accretion known as the Josephine Ophiolite. Plant communities are often defined by rock type, and this juncture creates unique plant assemblages. It is a place where complex rock interacts–nutrient rich soils of Coast Range meets the nutrient poor serpentines of the Josephine Ophiolite. It is also a place where ample rain falls, often in the amount of 100 inches per year. Because of these complex abiotic interactions, plants touch roots with plants in associations that almost never occur. For example, redwoods (Sequoia sempervirens) grow with pitcher plants (Darlingtonia californica) and western redcedars (Thuja plicata) with knobcone pines (Pinus attenuata).

Historically, the drainage saw major mining operations transform the landscape when placer mining (panning) in the late 1800’s gave way to the more destructive–and potentially more lucrative–hydraulic mining during the early 1900’s. Eventually, all the accessible gold was removed and as the miners left the landscape, it slowly recovered. Today, all that remains from the operations is a major sluice where the trail begins, a ditch upon which the trail is built as well as several old shafts that are fenced in for protection.

Pictured above is California pitcher plant (Darlingtonia californica) growing on serpentine, which is not unusual in Del Norte County. What is unusual is that along Myrtle Creek it associates with salal (Gaultheria shallon) which is in the picture and growing just above–casting shade–is a redwood tree.

- North Coast CNPS Page for Myrtle Creek Botanical Area

—–

COMMENT:

AUTHOR: Sue

DATE: 4/24/2014 4:18:08 PM

You said: “… a ditch upon which the trail is built…” This was no ditch, but a carefully constructed Chinese Footpath – the kind a person would see in Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos, or other Asian rainforest areas. In addition to a mining camp was a Chinese labor camp. They built the footpath – which used to extend from near the falls to what is now hwy 199. I have taken several Vietnam Veterans on this trail, and they are all amazed at the similarity between this “ditch” (as you call it) and trails they saw while in Vietnam. These Chinese trails are noted by drainage area on the ‘mountain’ side of the trail, and a berm on the “creek” side of the trail. This construction helps keep the trail intact despite wet weather. Unfortunately, after over 150 years, there have been some serious mudslides along the creek that covered portions of the footpath – making it very difficult to get to the falls. There are still gold mining claims along the creek, and in the past, these mining claims have been protected with rifles. But not any more. I love this creek, have hiked it for 40 years, and treasure the botanical life. But a well-maintained trail would be nice. I would love to be able to hike to the falls again on a real trail.

Sue- Thanks for the comment. Sounds like you have a great understanding and appreciation for this wonderful creek canyon. I am sorry if I offended you by calling it a ditch, I know better now! -Michael

Video: Foxtail pines across the Klamath Mountain Sky Islands

Juniperus occidentalis of the Yolla Bolly Explored | Papers w/ Robert Adams

Original Publication DATE: 9/3/2010 1:26:00 PM

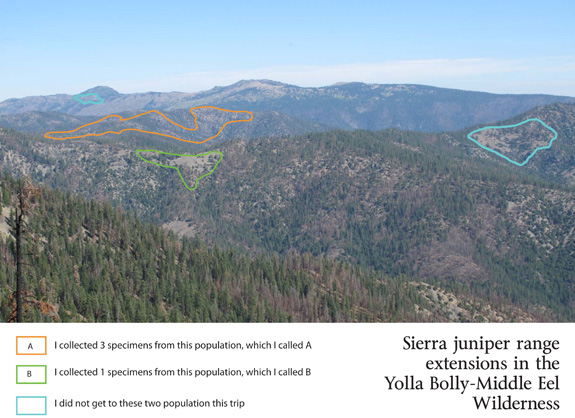

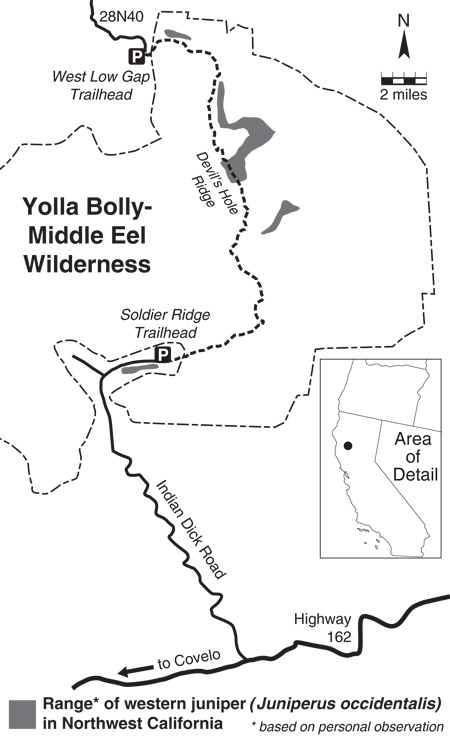

Late in the summer of 2009 I re-visited an isolated population of junipers in the Yolla Bolly-Middle Eel Wilderness. The visit was inspired by Robert Adams after he read a blog post of my first visit to the trees. At the time, the population was believed to be Juniperus grandis based on habitat type and other morphological characteristics. After collecting the specimens and sending them to Baylor University for study Dr. Adams published two papers last month on these populations and their relationship to other junipers of the west. He graciously named me as a co-author for my collecting and final editing skills–otherwise the work was all his.

The papers are:

- Geographic variation in the leaf essential oils of Juniperus grandis and comparison with J. occidentalis and J. osteosperma. Phytologia 92(2):167-185.

- Geographic variation in nrDNA and cp DNA of Juniperus californica, J. grandis, J. occidentalis and J. osteosperma (Cupressaceae). Phytologia 92(2):266-276.

While the DNA and essential oil comparisons verified the Yolla Bolly junipers are Juniper occidentalis they did not clarify the relationship of Juniperus occidentalis to Juniperus grandis. Unusual similarities were found between occidentalis populations of Oregon and Northern California and grandis populations of the San Bernardino Mountains. As Dr. Adams states in his conclusions, some questions were answered with the research but more questions remain–further study is needed.

—–

COMMENT:

AUTHOR: Jeffrey Kane

DATE: 9/6/2010 12:36:05 AM

yo dude. congrats on the pub(s).

—–

COMMENT:

AUTHOR: Dewey Robbins

DATE: 5/24/2014 5:10:10 PM

This population extends from Low Gap southwesterly along Jones Ridge nearly to Hayden Roughs as isolated individual. Most of the trees my forestry crew and I found were young regeneration; however, there are a few gnarled fire-scarred relics that are more like shrubs than trees.

—–

COMMENT:

AUTHOR: Michael E Kauffmann

DATE: 5/26/2014 2:58:05 PM

Dewey– thanks for the note. I’ve never been to that area of the Yolla-Bolly, but want to get there. It looks like they extend even further west to the Eaton Roughs. It is private property, but I’d love to get there too.

Stony Man Mountain | Shenandoah National Park

Original Publication Date: 11/26/2010

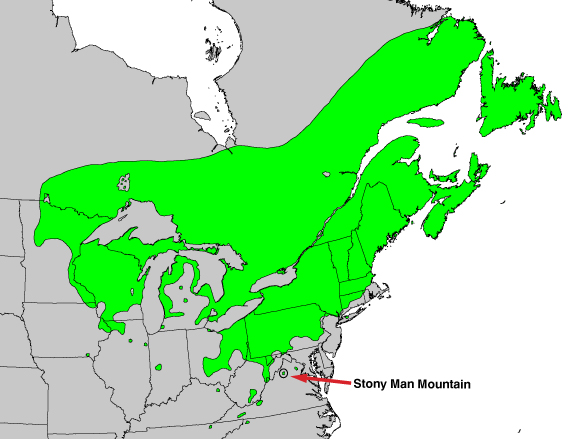

Botanists and ecologists familiar with the Klamath Mountains are inevitably familiar with the similarities the area has with the southern Appalachian Mountains. It is understood that both regions harbor exceptional plant diversity due to the complex interaction of several factors. They are each ancient mountain ranges that have sustained a similar flora since at least the Cenozoic. These mountainous regions have served as monadnocks–ultimately refuges for plants as populations of species have been eliminated by glaciation and climatic dessication1. Arriving in Virginia in a warm, dry November spell the Blue Ridge Mountains were beckoning me to visit as I peered toward them from the Shenandoah Valley.

I decided to research a mountain top hike that would provide both views and of course–if possible–relict conifers. After finding a publication from 1966 about the conifers of Shenandoah National Park2 mom, dad, and I settled on Stony Man Mountain–the second highest peak in the park at 4010 feet. The Appalachians have an ancient history, being one of the oldest mountain ranges in the world. Stony Man’s summit is composed of greenstones–which were formed 800 million years ago (Ma) by lava flow. With time the rocks changed and were ultimately uplifted 200 Ma and have eroded back to their current height over millenia. The botanical interests–while dependant on the mountain for safe harbor–are a more recent circumstance.

In addition to the wide array of flowering trees, shrubs and annuals that can be found in the Appalachians, several relict conifers survive on this particular mountain top and sporadically elsewhere across the rolling landscape. The conifers are harbingers for the microsites fostered by complex climate and geology which ultimately mimic conditions of a colder time. Canada yew (Taxus canadensis), red spruce (Picea rubens), and balsam fir (Abies balsamea) are found at their southern range extensions in and around the southern Appalachians of Virginia. These trees thrived in the colder climate of the Pleistocene but are now restricted to the highest mountain tops and coolest glades.

Canada Yew | Taxus canadensis

The Canada yew is an understory tree of late successional forests. This is exactly the habitat in which we found it in Shenandoah National Park. This yew of the northeast is ecologically identical to the Pacific yew (Taxus brevifolia) of the Pacific northwest. The small isolated population we found on the summit of Stony Man reminded me of select mountain tops of the Klamath–like Preston Peak. The population here was matted to the earth and often growing beneath and around shrubs on rocky outcrops punished by the elements.

Needless to say, this was an exciting plant to find and learn about...as were those that follow but are discussed in less detail.

A few other conifer highlights included…

Balsam fir | Abies balsamea

- Conifers.org balsam fir

- Wikipedia balsam fir

- Conifers.org Frasier fir

- Evolutionary history of the two species

red spruce | Picea rubens

pitch pine | Pinus rigida

Other Resources:

Citations:

- Whittaker, R. H. 1960. Vegetation of the Siskiyou Mountains, Oregon and California. Ecological Monographs. V30:3:279-338.

- Mazzeo, Peter M. 1966. Notes on the Conifers of the Shenandoah National Park. Castanea 31:3: 240-247.

- Hils, Matthew H. 1993. Taxaceae. Flora of North America Editorial Committee (eds.): Flora of North America North of Mexico, Vol. 2. Oxford University Press.

- Potter, K.M. et al. 2010. Evolutionary history of two endemic Appalachian conifers revealed using microsattilite markers. Conversation genetics. 11:1499-1513.

- Farjon, Aljos. 1990. Pinaceae: drawings and descriptions of the genera Abies, Cedrus, Pseudolarix, Keteleeria, Nothotsuga, Tsuga, Cathaya, Pseudotsuga, Larix and Picea. Königstein: Koeltz Scientific Books

COMMENT:

AUTHOR: David Fix

DATE: 11/24/2010 2:17:02 PM

Thank you, Michael, for the quick look-see. Jude and I were in the park, as well as over in the Alleghenies in May and also enjoyed Red Spruce. It was fun to see you apply your landscape-parsing and plant skills to a different place. Question. What is that abundant and delicate knee-high fern with the pinnae that barely clasp your fingers as you feel it? But I simply enjoyed it in many spots and don’t need the name…

—–

COMMENT:

AUTHOR: Allison

DATE: 11/24/2010 2:43:10 PM

Great trip, beautiful! This also taught me that monadnock is not just a mountain in southern New Hampshire, but rather my favorite mountain is the name sake for the topographical phenomenon.

Canyon Creek Brewer Spruce | Trinity Alps Wilderness

Original Publication DATE: 9/27/2010